The Story

of

Ms. Starks

A Case of Depression, High Blood Pressure, and High Cholesterol

Ms. Starks’ hugs make you feel like you can conquer anything. It is an innate strength of her that shines through all her interactions with you. Now in her late 40s, Ms. Starks surrounds herself with the support of her five sons; three of whom she had with her previous partner and two of whom she adopted. Three of them have gone to live independently, but check in with her on a consistent basis. For her, the belief that she will survive anything with her boys—or her “pack of wolves” as she calls them—is what gives Ms. Starks a solve-everything-and-anything attitude. That, and her faith in God.

But an unexpected eviction notice robbed her from that belief in herself.

I first met Ms. Starks at Ms. Jennie’s Place Community Enrichment Center—a teaching space aimed at helping those experiencing homelessness, abuse, substance dependency, and difficult educational experiences “be able to return to society as a complete, nurtured and productive member.” Ms. Jennie’s Place exists in East Durham, a neighborhood at the heart of displacement trends in the city. Ms. Starks is not there as a recipient, but as a partner for the Center through Network of Families as their Executive Director. The Network of Families works to feed families in the Durham Public Schools.

Ms. Starks is no stranger to trauma, loss, and economic struggle. At least, not personally. Families unable to obtain food or find proper care for their children find themselves going to Ms. Starks’ group for support. So when Ms. Starks received an eviction notice from Mr. Joe Hicks (landlord) in November 2018, a wave of shame hit her. This shame was compounded by the stress she experienced in the months leading to the eviction notice. Ms. Starks’ story reveals a mother, a caretaker, a spiritual woman, who has displayed resilience despite the unexpected circumstances out of her control. It represents the story of a tenant who is acutely aware of the gentrification occurring in the city but continues pushing ahead. Praying for peace.

Threatened Security

“I always thought evictions for people who did not take care of their business. And that was one of the things that I prided myself on, that that was the first bill I paid because I felt like, you know, I call my boys my wolves. I felt like the wolves always had to have a den. You can't holler at the moon all night, you gotta go in the den [...] And to have that security threatened, um, and not know what to do was very, very, um, disconcerting.”

- Ms. Starks (2018)

Events Leading to the Eviction

Ms. Starks describes her landlord, Mr. Hicks, as a “very boisterous, loud person,” a white man in his late sixties. Prior to the eviction notice, she never had any problems with him: “he's never actually been to my house. But he’s seen me at the office plenty of times, or he's talked to me on the phone when things have, you know, broken in the house or whatever. Over the years, um, they've always been taken care of in a timely manner.” She shares that she’s been blessed to never have experienced the poor service that Mr. Hicks’ reputation carries, as a Yelp reviewer posted in February 2019, “Mr. Southern Sweet Joe maybe be the cheapest guy in town, but as a tenant, [the] situation is beyond frustrating.”

She had been living in one of Mr. Hicks’ managed properties for eight years, in a three-bedroom, one-bathroom house in the Braggtown neighborhood. The house lacks natural light. It has remnants of half-fixed walls and appliances, and is cluttered and packed with food supplies for her organization, along with food for her boys. It’s among several houses Mr. Hicks rents out in the neighborhood, mostly to low-income Latinx and Black tenants. Ms. Starks was paying $800 a month for rent with the support of her Section 8 voucher.

On August 27, 2018, Mr. Hicks notified Ms. Starks that she needed to move out by the end of September. He planned to sell the house on behalf of the owner. Ms. Starks was grateful for the extra few days’ notice, “he is not required to do that, only a 30-day notice,” she said. After her one-year lease ended nearly seven years ago, it automatically converted to a month-to-month lease.

Ms. Starks’ Story in Pictures (click on thumbnails to magnify images and read her story)

Mr. Hicks’ Response to her Second Extension Request

I was caught so off guard when I was trying to explain to him that I had a place, but it was taken longer than usual, that he was saying, you know, [in an angry tone] ‘Get out! I don't care what you do! Go stay with your mom or just put yourself on the street. I don't care.’

For him to have that attitude is very, very different from the person that you know, I've known over these years.

-Ms. Starks (2019)

Throughout September, Ms. Starks spent her free time searching for a new house large enough for her dog and two sons—one in high school, and the other in middle school. She also wanted to ensure her sons remained in the same school to encourage stability. Much to her dismay, every place she found was more than $1,000 per month.

She asked Mr. Hicks for an extension at the end of September for the month of October. He accepted it. She continued searching. Towards the middle of the month, Ms. Starks finally found Briar Green Apartments, an affordable housing community only a few minutes from her current house. Briar Green Apartments would accept her voucher. The only problem is that the complex did not have any three-bedroom apartment available until December. Three bedrooms were necessary given one of her son’s mental health status. One thing her son’s counselors “stressed really hard is that he needs his own room. He has to have an area where he can go in the dark and, and, um, settle his self down.”

Ms. Starks asked for a second extension once she found out about the wait for an apartment, informing Mr. Hicks that she needed additional time to wait until the apartment was available. His response was a surprise to her. According to Ms. Starks, he talked to her like she was “trash” and continued to say “I don’t care!” She pleaded for more time. “I didn’t want to go to the shelter” because her boys would be required to sleep with the men, and she was not sure what would happen there with her son who needed to be by her side.

She decided to avoid being homeless and told Mr. Hicks that she was going to stay there until the apartment was ready. And “I’m going to pray.” After this, his calls became more frequent. “I’m going to take that HUD voucher away from you,” he threatened.

Despite these reactions from Mr. Hicks, he still took Ms. Starks’ November rent. And he gave her a 10-day grace period to move—this is one of the requirements for a landlord to file a summary ejectment for hold over, which is when the tenant refuses to leave the property.

Around this time in October, Ms. Starks was due for her annual physical check-up—the only time she visited the hospital besides for her son’s medical care. She had a relatively healthy history, with the only health concern being her overweight status. Her blood sugar was normal for years despite her weight. In general, she was able to manage it well with no issues.

During her appointment, her practitioner noticed her blood pressure was significantly higher than usual. “My blood pressure was like off the scale. Like a lot of nights just so stressed out.” She also started overeating as a way to cope with the stress. When her practitioner asked her what was happening in her life, she “couldn't share with him that, you know, I'm possibly being evicted. I just told [the doctor] I was super stressed. A lot was going on. And he automatically assumed it was about [my son] because, um, he was in a mental health facility in [another city] and they wanted to release him to come home before Christmas. And, um, I could not tell them I was going to be evicted because I couldn't have been able to get my own child back.”

Her general practitioner prescribed her medication for high blood pressure and high cholesterol. She now needed to take three different pills. Prior to this point, she had never been on any prescription drugs. However, her Medicaid plan covered most of the expenses, with her only having a co-pay of $3 per medication. They set up another appointment to check on the status of her blood pressure in late December.

The Notice

After the 10-day grace period in October, Mr. Hicks officially filed a summary ejectment for hold over at the end of the month. Hold over is when a tenant refuses to leave the property past their lease agreement.

The eviction notice gave Ms. Starks a sense of massive humiliation she had never experienced before. When I first heard Ms. Starks share this part of the story, she kept using words like “shame” and “embarrassed,” sometimes in between tears. She always thought evictions were “for people who did not take care of their business. And that was one of the things that I prided myself on, that that was the first bill I paid because I felt like, you know, I call my boys my wolves. I felt like the wolves always had to have a den. You can't holler at the moon all night, you gotta go in the den [...] And to have that security threatened, um, and not know what to do was very, very, um, disconcerting.”

When Ms. Starks received the notice, she also received a flyer from the Durham Eviction Diversion Program. She had never heard of them, but decided to immediately seek their help. Her court date was set for late November. Brent Ducharme was assigned to her case. Mr. Ducharme is one of four full-time staff attorneys representing tenants in the County. He has worked for the Durham Eviction Diversion Program since its inception, believing that until the government provides housing for all low-income residents, legal representation is the best way to avoid an eviction.

According to Ms. Starks, Mr. Ducharme informed her that she did not need to attend court because they could handle it. But she told him, “I’m going to show up [to court] because I’m a responsible person.” She believed she did nothing wrong to be evicted. “All I was asking for is time; I was paying my rent. I was responsible.”

During the time leading up to the eviction hearing, Ms. Starks started feeling a “general sickness” that “hung over me, just wanting to avoid, you know, leaving.” Her language—with descriptions like “putting one foot in front of the other and not really in the moment”—reflected someone who was experiencing depression—something she claimed she never had.

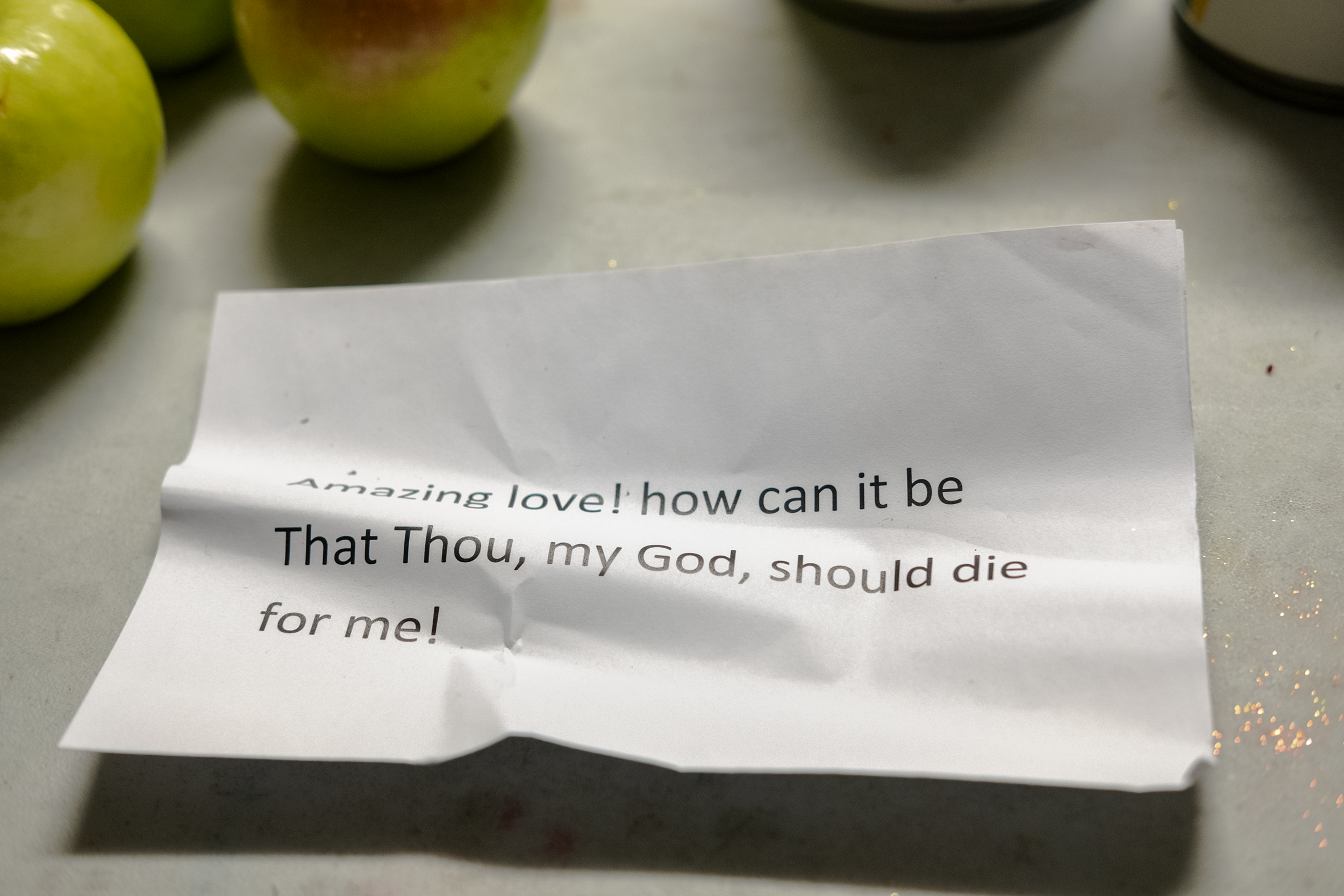

Her depression also affected her faith. Prior to her notice, she attended church religiously every Sunday. Then she started missing services, or going really late because she couldn’t get dressed. “I just didn’t want to do it. And the only thing that kept me strong was my boys. I didn’t want them to know.” When her church family asked what was happening, “I was too ashamed to admit it was an eviction, I was just saying that after all these years of living in the house, my landlord wants me to move because he wants more rent. And they were like, ‘don’t worry. God got a plan.’

Hold Over From a Landlord’s Perspective

I spoke to one of Durham’s most prominent landlords about hold over evictions. He oversees about 900 low-income tenants at any given time and frequently finds himself in small claims court to evict tenants for nonpayment of rent. While I sat at District Court to hear some of the eviction cases, I saw him informing the magistrate that “maybe we could work something out” with one tenant who was behind on rent to avoid having them lose their Section 8 voucher despite his summary ejectment filing.

In my meeting with this landlord, he shared that he takes tenants to court as a last resort. “They [the tenants] are not bad people. It’s about the money,” he shared. However, he does not deal with hold over evictions because he finds it wrong to kick someone out of their home if they have been living there for years. If his homeowners want to sell the property, “we make sure we find housing for the tenants” to move or set the renters up with a plan so they are not fending for themselves.

The Court Case

In preparation for the case, Brent met with Ms. Starks to brief her on the process and the likelihood of them winning. The chances were 50-50. But the fact that she paid rent and Mr. Hicks had accepted it was “really a feather in my cap.” However, he wanted her to be prepared for any outcome. Even if they evicted her, she would have other options. “I was grateful for that because [court is] a world I don’t know. If it’s about a hungry child or a child that needs an individual education plan or can’t get help in school, I know all about that. But this was like, I had no idea.”

On the day of the court hearing, she sat near Brent. Their case was called up by the magistrate, who Ms. Starks describes as “extremely professional.” The magistrate expressed surprise to see Ms. Starks in court with legal assistance (“I didn’t know if it was a surprise good or a surprise bad,” she recalls). Even Mr. Hicks was surprised to see her there. In my days sitting in housing court to hear eviction cases during this project, I rarely saw tenants come with representation, harking on The Durham Human Relations Commission’s (2018) statistic that 95% of tenants do not have legal representation.

Mr. Hicks took control of the hearing according to Ms. Starks. She notes that he was being friendly and all “buddy-buddy” with the magistrate, and that he used this “as an intimidation” tactic. During the hearing, Mr. Hicks told the magistrate that Ms. Starks refused to leave the house, and to bolster his argument, he mentioned that Ms. Starks was late on rent three times. “Three times in eight years? But that’s not what you’re bringing her here for” noted the magistrate.

Mr. Hicks submitted the rent ledger with Ms. Starks rental payment record to show her late payments. In it, there was evidence that he accepted November’s rent despite putting the notice to have her out that month. As the magistrate stated, “You took her money.”

The magistrate denied the landlord’s complaint given that Brent and Ms. Starks proved their case. She avoided the eviction. Mr. Hicks and Ms. Starks then negotiated for a December 31 move out while she prepared to move to Briar Green Apartments.

Orange Signs

Beyond Ms. Starks’ fear of losing her voucher, she was afraid that the circumstances might push her underaged kids to engage in criminal activities to protect her despite all of her teachings.

'“[My son] doesn't understand why. He's like, ‘you're paying the rent, you know, we're here. oh, why do people have to be so greedy?’

And he says, you know, ‘I don't want our house to be the house with the orange sign.’ You know, that they put in the houses when there is an eviction, it's always an orange sign. And he said, ‘I don't, I don't want to see that. I don't want to see us sleeping in the car.’ You know, and um, you know, his theory is ‘I'll do whatever I have to do. You know, I got friends that say there was a way for me to get money and stuff.’ I'm like, Oh my God, you know, all my work is…[long pause].

-Ms. Starks (2019)

The door of Ms. Starks’ home in anticipation for Holy Week. Photo by Karla Jimenez-Magdaleno, 2019.

The Aftermath

“Going to court helped me to know that sometimes you gotta fight,” Ms. Starks told me. Yet, even though she won, she still feels the “heaviness of shame,” no matter how much she can rationalize that this was out of her control. By the time she was ready move and her son returned home from the treatment facility, a snow storm hit Durham, slowing down any potential moves. So she stayed an extra month to the end of January. And another. And another.

It was not until one of my last meetings with Ms. Starks in March that she admitted being on antidepressants. Her doctor prescribed it to her in late December, several weeks after winning her case. She is hesitant to share that aspect of her health with others.

Traumatic

…even in the work that I do that I'm helping people that don't have food and, um, don't have clothes and things like that. And, and I'm really going through something just as traumatic and I'm hoping it makes me better.

-Ms. Starks (2019)

She also continues her now-routine visit to the doctor, scheduled for every two months, up from the sole annual visitation she used to need. Still she takes four different medications a day.

She continues facing delays in her move; her health conditions have only improved marginally. Ms. Starks expected to move by the end of March, but her plans were delayed when she received a call about her mother’s passing on March 30. Her mother was struck by a vehicle on her way to the hospital. Ms. Starks is trying to stay strong, for her boys. “I want to show them what you do in the face of uncertainty, and um, handle yourself with grace.” They will spend a week to mourn after they move sometime in April.

In a meeting in March, she heard that Durham Housing Authority will become one of the only housing authorities in the nation to create a homeownership program for tenants with Section 8 vouchers. She put her name on the list. “God is giving me little blessings to say, ‘come on, Sheri, don’t lose faith.’”

As of April 1, 2019, Ms. Starks is still in the same house. Only for a few more days as the apartment at Brier Green waits for her. Her kitchen pantries remain empty while her living room surfaces overflow with food pantry supplies, half-packed boxes, and other clutter. Eight years worth of belongings and memories to be left behind because of one eviction notice.

Story and photographs by Karla Jimenez-Magdaleno (2019).