Downtown Durham skyline. 2017. Photo credit: Karla Jimenez-Magdaleno

Eviction and Gentrification

Beyond understand the process of an eviction, it is imperative to also understand the connection between gentrification and eviction.

Evictions are often perceived as being a symptom of gentrification. This project uses Lisa Bates’ (2013) definition of gentrification, which defines the phenomenon as a neighborhood change process involving:

increased public and private investment;

rapid increases in housing prices; and

demographic and economic shifts in an area that result in experiences of housing instability for a segment of residents living in the area, often vulnerable racial/ethnic populations.

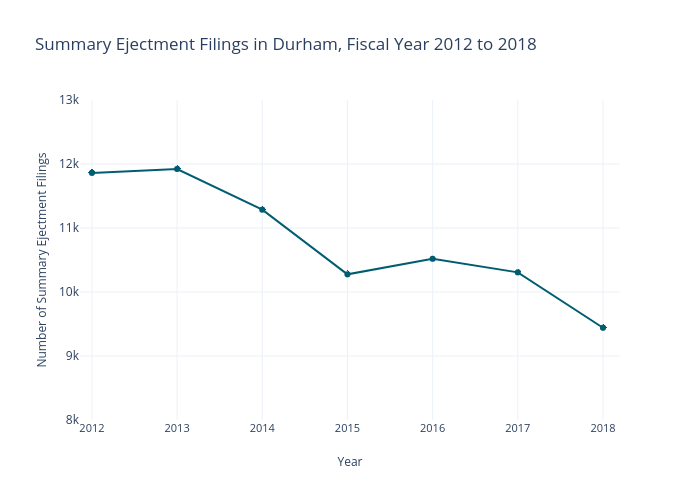

The logic follows that neighborhoods in early stages of gentrification (marked by rising property values, stagnant/unequal wages, and demographic changes) are more likely to experience an increase in evictions; further, the limited national data that exist on evictions indicate that cities with the highest rates of evictions are often ranked as affordable and up-and-coming places to live. Cities with neighborhoods in the midst of late-stage gentrification, like Washington, D.C., or Austin, TX, have eviction rates at or below the national average compared to large or midsize southern cities in early- to mid-stages of gentrification, like North Charleston, SC, or Durham, NC. This trend suggests that the relationship between gentrification and evictions is temporally-dependent, and in need of more understanding as southern cities continue to be at the forefront of this issue.

Below is a map developed by the Pew Charitable Trust using data from the Eviction Lab. It displays the eviction rates among large and mid-size cities in the United States for 2016, highlighting how landlords are filing the bulk of evictions in the south and mid-Atlantic region